Invisible Arteries: Subsea Cables in the Age of AI

The glass threads under the sea matter as much as chips and data centers and Asia’s AI boom depends on who controls them

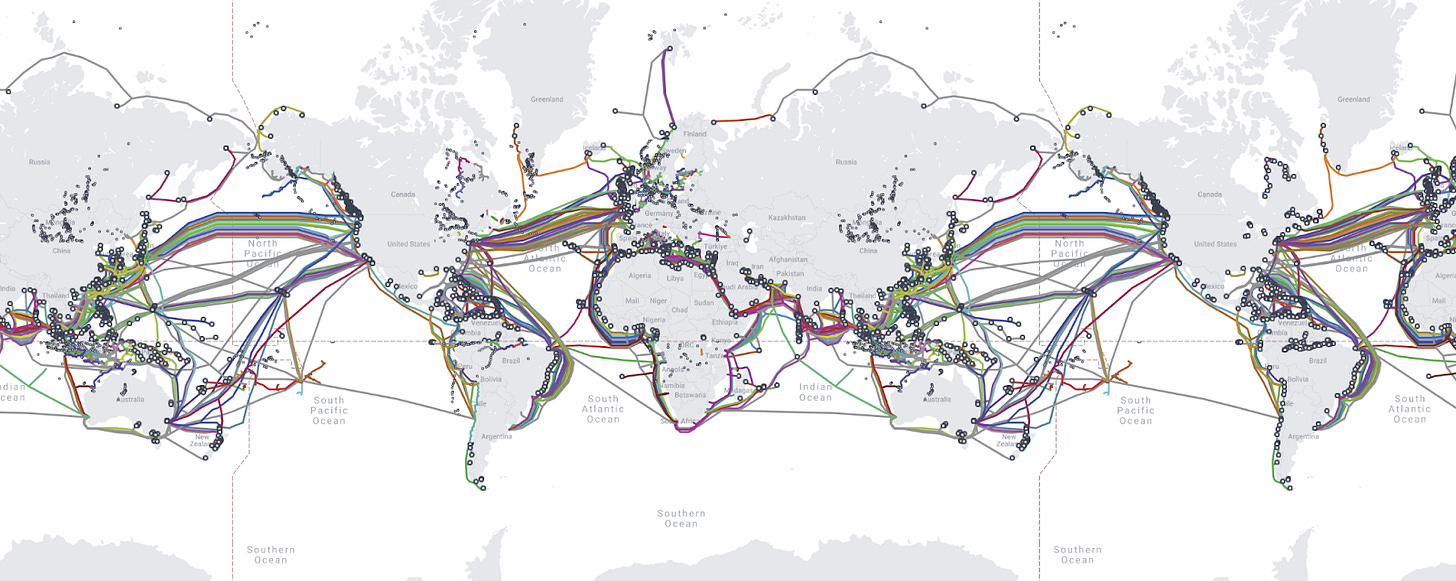

Every click, every call, every binge-watch. Even the fact that you are reading this article right now. All of it travels through subsea cables: bundles of fiber-optic glass threads, often no thicker than a garden hose, lying silently on the ocean floor. We don’t talk about them much, but they are the invisible arteries of the internet, carrying 95% of intercontinental internet traffic. As of early 2025, TeleGeography counts 600 submarine cables, spanning over 1.48 million kilometers in service and yet, for all their reach, they remain as fragile as they are vital.

Last week’s Red Sea outage was a sharp reminder of just how fragile that system is. Several cables were severed, forcing Microsoft to reroute traffic and slowing internet speeds across at least 10 countries from India to East Africa.

For Asia’s AI future, the real story isn’t just chips and data centers. It’s the invisible glass threads under the sea - the arteries of the internet that connect cloud campuses, carry model weights, and keep the region’s digital economy alive.

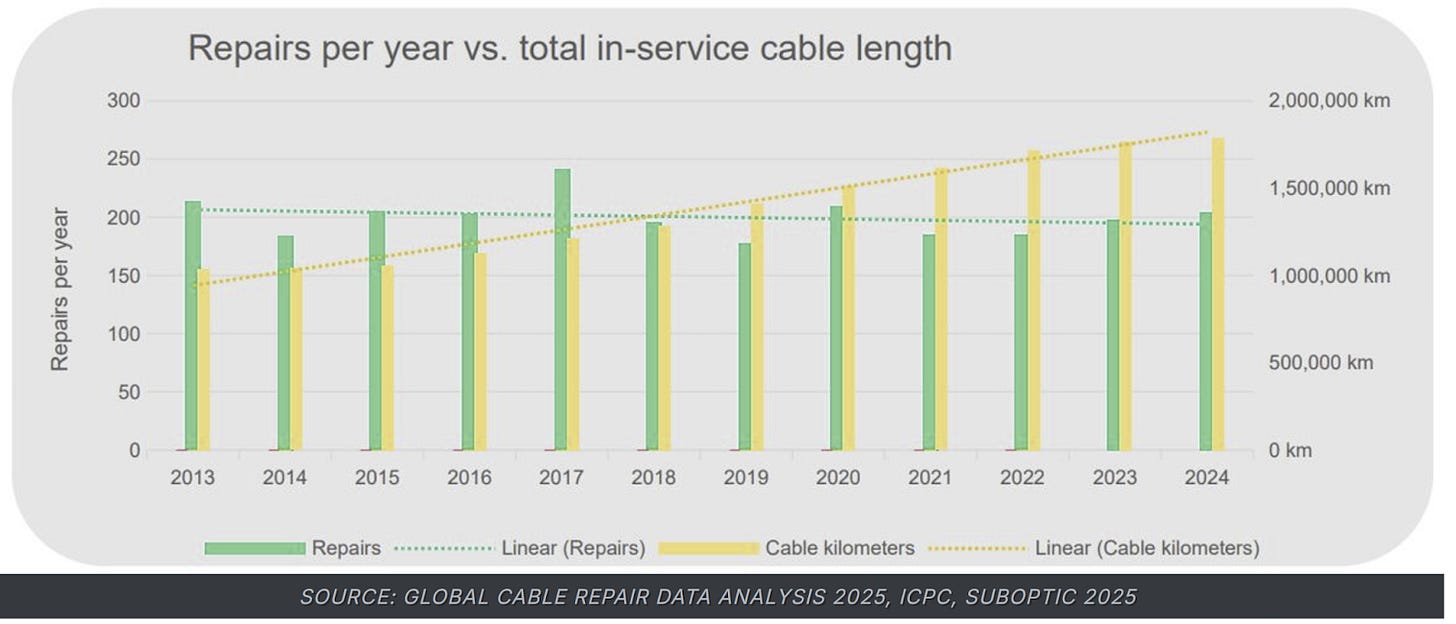

Incidents like this aren’t rare. While the cause is still under investigation, experts say the usual culprits are ship anchors, fishing trawlers, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or even sabotage. Every year, there are an average of around 200 cable-related faults according to data from the International Cable Protection Committee. Repairs are tough, costly, needing specialized ships and crews that can take weeks to bring the cables back online. According to the ICPC, there were 206 repairs in 2023 with the longest repair taking 947 days.

Asia’s Digital Ports

Asia is in the middle of a digital construction boom. Billions are being poured into data centers, cloud campuses, and AI infrastructure. But servers alone don’t do the job. Every model trained, every data set processed, every cloud service delivered still depends on subsea cables to ferry data in and out of the region.

That’s why cable landings are often called the new ports of the digital economy. If maritime ports once determined the flow of goods, subsea cables now determine the flow of data. It’s no wonder that countries in southeast Asia such as Malaysia, Singapore and Philippines have been ramping up efforts to boost their subsea cable capabilities.

Singapore is the region’s main digital gateway. It serves as a landing station for more than two dozen subsea cable systems, acting like one of the key entry and exit points for global internet traffic flowing between Asia, the U.S., and Europe. The government plans to double that landing capacity over the next decade. One big project is the Bifrost Cable System, a US$760 million trans-Pacific cable backed by Meta, Keppel, and Telkom Indonesia, that will directly link Singapore to the U.S. West Coast when it goes live in 2025. It’s also the first new system on that route in eight years. Another is SEA-ME-WE 6, connecting Southeast Asia to Europe through the Middle East, with Singapore as a key landing site. This connectivity is the reason tech giants like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google have clustered their cloud and data center operations in Singapore.

Malaysia currently operates six cable landing stations and is connected to 29 submarine cable systems, including those under construction. Most of these systems land on Peninsular Malaysia, including in Johor, which has become a spillover site for hyperscalers that want alternatives to Singapore’s tighter land and energy limits. Projects like the MIST cable, linking Malaysia, India, Singapore, and Thailand with over 200 Tera-bits per second of capacity, reflect how the country is positioning itself as both a redundancy option and a rising hub in its own right.

The Philippines is also climbing the digital ladder. Google and Meta have chosen it for systems like Apricot, a high-speed cable connecting Japan, Guam, and Southeast Asia that will land in Manila and Davao. For a country long seen as just a consumer market, these projects signal a shift, turning the Philippines into a genuine transit point for data flows across the Pacific and Asia.

Taiwan highlights the risks. The island has faced repeated cable cuts, often blamed on fishing vessels, which have disrupted connectivity and forced reliance on backup satellite links. In 2023, two major cables connecting Taiwan’s Matsu Islands were severed, leaving residents cut off for weeks. For a place so central to the global chip industry, these incidents are a glaring vulnerability and a stark reminder of why control over cable landings is a critical issue as we move into a more AI-driven world.

Who Owns These Cables

For decades, subsea cables were owned and operated by telecom carriers. That’s changing fast. Today, the biggest drivers are the hyperscalers - Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon, who no longer just lease capacity, but design and fund entire systems to serve their own AI and cloud workloads.

Google leads the pack with more than 30 cable systems worldwide. Meta isn’t far behind with investments in over 20 projects including Project Waterworth. When completed, it will be the world’s longest subsea cable project, spanning over 50,000 kilometers. Amazon and Microsoft are ramping up as well, backing new trans-Pacific and intra-Asia routes tailored for their cloud businesses.

Unlike the West’s corporate model, China’s systems are backed by state financing and policy, embedding geopolitical considerations directly into the architecture of global connectivity. HMN Tech and China Unicom operate as both commercial firms and instruments of national strategy, aligning closely with government initiatives like the Digital Silk Road and the Belt and Road Initiative. HMN Tech alone has been involved in more than 90 international cable projects, highlighting its central role in expanding China’s digital reach.

Why does that matter?

First, owning the cables means controlling the bandwidth. For companies that process millions of gigabytes of data every day, even a small improvement in speed can mean huge savings and competitive advantage. It also reduces their dependence on third-party operators, letting them manage traffic on their own terms.

Second, it raises national security concerns. When critical infrastructure is owned by private corporations, governments lose some oversight. Who decides where data travels, or who gets priority during outages? These questions become even sharper in times of geopolitical tension. We’ve already seen projects cancelled or rerouted, like the Pacific Light Cable Network, which dropped its planned Hong Kong landing after U.S. officials raised concerns over Chinese government access.

What’s at Stake?

We tend to fixate on chips, but moving data quickly and reliably across oceans matters just as much. Outages mean bottlenecks, higher costs, and delayed innovation.

The risks are real, but the legal framework that governs them is comparatively weak. Current rules fall under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a framework written for shipping and fisheries, not for critical digital infrastructure. When a cable is cut in international waters, whether by accident or sabotage, there is no effective regime to hold perpetrators accountable. The jurisdiction lies with the state under whose flag the ship operates or that of the person’s citizenship and not the state that owns the cable.

For Asia, that gap is especially risky. The region is both the fastest-growing market for cloud and AI services and the crossroads of U.S. and Chinese cable systems. With so much of the world’s data flowing into the region, weak governance leaves Asia dangerously exposed to both accidental outages and targeted interference.

Without stronger global safeguards, Asia’s AI boom risks being built on fragile foundations. Subsea cables may be invisible, but they are the bedrock of the region’s digital future and right now that bedrock is far too easy to crack.

For More Info on Asia Tech Lens