Why Japan’s Quantum Strategy Starts With Algorithms, Not Qubits

While global attention has been on hardware, companies like Japan’s QunaSys are advancing algorithms and software to make quantum useful

There is a good reason to look at Japan as a reference point for where quantum computing may actually go next. Players in the country are grappling with a question that is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore as governments and tech giants race to build ever-larger quantum machines: will these systems ever do anything useful?

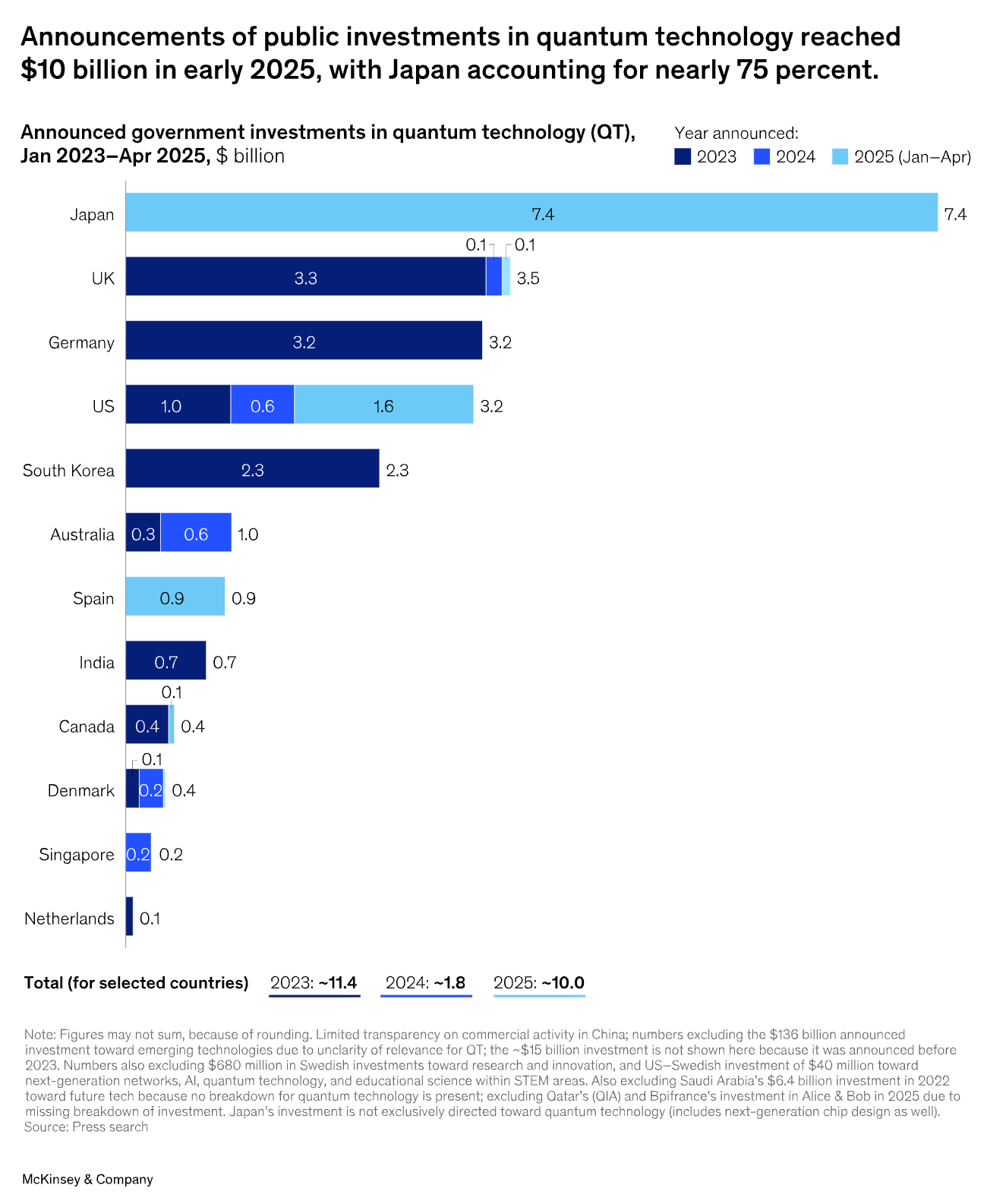

2025 has become a milestone year for quantum technology. Designated the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, it has also coincided with a surge in investment. Over the past year, the sector has attracted more than US$4.16 billion in funding, a 99% increase from 2024.

While much of the global spotlight remains on the United States—which hosts the largest number of quantum computing startups and some of the sector’s biggest fundraises—Japan’s ambition to emerge as a quantum frontrunner deserves attention. Earlier this year, the government unveiled a US$7.4 billion initiative to support its domestic quantum industry, accounting for nearly 75% of global government quantum investments in early 2025, according to McKinsey & Company.

One way to see how this strategy plays out in practice is through QunaSys, a Tokyo-based company founded in 2018. It specialises in developing quantum algorithms and software for chemistry applications. The company has raised US$23.7 million to date. Its choice in focusing on building use cases for quantum technology stands apart in a hardware-first industry where actors race to build ever-larger machines.

An Incentive Mismatch

To understand why this approach is notable, it helps to look at the incentive structure shaping the quantum industry.

In approximately the last 30 years, quantum processors have scaled up from a 2-qubit machine to surpassing 1,000 qubits. IBM, for one, has set a milestone to reach a 100,000-qubit system by 2033. But these numbers are symbolic rather than decisive. More qubits do not automatically translate into usable computation, especially when error rates tend to rise as systems scale. So far, incentives have favored scaling hardware over developing software.

Hardware development is rewarded early and often. That is because hardware progress can be quantified—more qubits, improved error rates—and it is tied to narratives of national competitiveness and technological sovereignty. Use cases, while desirable, are not a prerequisite. Quantum software operates under very different constraints. Its value depends on hardware, and thus, has traditionally been treated as something that will matter “later”, once hardware reaches a certain threshold.

In recent years, however, the dynamic has begun to shift. According to a 2024 McKinsey report, most new startups launched in 2024 are developing equipment and components or application software. “Overall, we anticipate a value shift with QT [quantum technology] start-ups moving from hardware to software in the next five to ten years,” the report writes. It seems to be the case that the inflection point in quantum includes a shift in attention for quantum software. The hardware has grown to a point where it makes sense to start looking for applications.

Still, the core paradox remains. Quantum software must be useful before hardware is truly ready, yet realistic about what today’s machines can handle. This tension sits at the heart of the field and defines the challenge companies like QunaSys are trying to solve.

How To Build Use Cases

QunaSys is a niche player by design. It distinguishes itself from other quantum players who are building a full-stack offering. Such an approach is guided by gaps seen in the industry. “A common misunderstanding is that if we have a quantum computer, it can calculate exponentially fast. That’s not actually the case. We need clever algorithms that use the best out of this quantum computer,” Tennin Yan, the co-founder and CEO of QunaSys said in a panel earlier this year.

In a field still searching for real-world applications, the company’s focus on algorithms and software could very well be its strength. It allows the company to focus on partnerships aimed at exploring where quantum could be useful, resulting in several early use cases.

One example the CEO gave during the panel talk was the company’s partnership with Toyota Motors. Toyota needed a more precise calculation to build batteries. To do so, QunaSys carried out multiple resource estimations—calculations of the computational cost for simulating molecules. These exercises likely do not represent production-ready breakthroughs, but they help companies understand what quantum methods might enable, and what they will require, in the future.

Toyota is far from being the only company who has partnered up with QunaSys. In fact, through a consortium it established in 2020 called QPARC, QunaSys has engaged and collaborated with over 50 companies to develop quantum computing algorithms and applications to solve industrial problems. “We believe that it is crucial to get ready to position ourselves at the forefront for the quantum computing revolution for when the hardware reaches its full potential,” the company writes of its consortium.

One example the company shared in a presentation was of its partner having found a new reaction path through QunaSys’ quantum chemistry software, Qamuy. Said partner wasn’t able to make the discovery through conventional software. These are exploratory advantages, but they illustrate how quantum software can extend existing workflows.

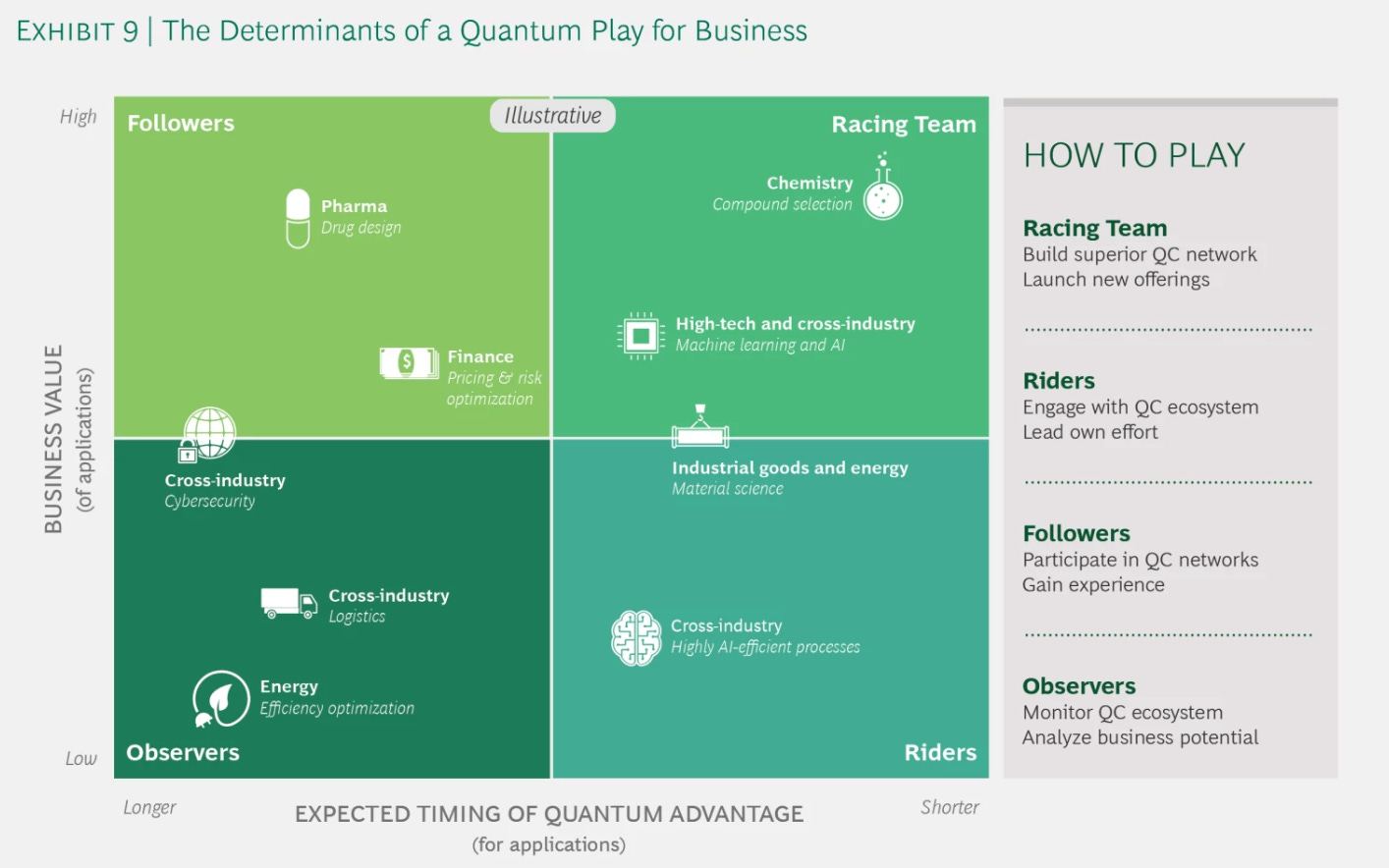

What does all this point towards? QunaSys has positioned itself strategically to deliver near-term business benefits for its partners, which is not something that is a given in the world of quantum computing. This serves to highlight the clever bet on specializing in quantum chemistry. According to a report published by BCG, quantum chemistry has the highest tangible promise of applications. This is the field where the expected time frame to quantum advantage is the shortest and the potential business benefit is high.

Driving Momentum Forward

QunaSys’ approach to ecosystem-building is something that can be used as a reference point for other quantum players. Not only is it forming a network of strategic partners to explore quantum use cases, embedded in its ecosystem-building strategy is the intention to future-proof and go global.

On the former, QunaSys is committed to the work of nurturing the next generation of talent in quantum chemistry. It organizes training programs, workshops, and hackathons—events that have seen over 170 students participating and over 150 employees trained to work in quantum computing (according to 2022 figures shared in a presentation).

On its global project, the company is known to have built strong partnerships with relevant stakeholders in the U.S. and Europe. It is connected to the U.S. quantum ecosystem through its relationship with IBM—QunaSys is a member of the IBM Quantum Network, as well as an investee of IBM Ventures—and the Pistoia Alliance, which connects QunaSys with global life science players. QunaSys’ presence in Europe is marked with its recent membership in EU Sustainable Battery Innovation Consortium.

These partnerships signal interoperability with the U.S. hardware ecosystem, credibility with life sciences and battery research, as well as Japan’s positioning as a software and application node, not a standalone ecosystem.

Seen in this light, Japan’s quantum strategy looks less like a moonshot and more like industrial policy: slower, more methodical, and oriented toward use. While other countries compete to build the biggest machines, Japan is investing in the connective tissue that determines whether those machines will matter.

QunaSys does not offer a shortcut to quantum advantage. What it offers instead is a model for how quantum computing might earn its place—by prioritizing usefulness over spectacle. In a field defined by long timelines, that may prove to be one of the most pragmatic bets of all.

Related Reading On Asia Tech Lens

If this piece resonated, here is where the same questions about capability, incentives, and real-world utility are showing up across Asia’s tech stack:

Can India Build Quantum Computers That Matter Globally?

Why India’s quantum ambitions ultimately hinge on talent, supply chains, and credible use cases more than milestone announcements.

Singapore’s Quantum Bet: Where AI Meets the Next Compute Revolution

How Singapore is trying to turn quantum into near-term hybrid experimentation and ecosystem capability, not just a qubit race.

The Dependency Economy of AI: Sovereignty, Chips, and Global Chokepoints

This article distills the key insights from Damien Kopp’s white paper, providing a high-level look at the sovereignty fault lines shaping the global AI landscape.

The Chip War’s New Reality: A View from the Crossroads

An Op-ed on what a trade-exposed hub like Singapore sees when export controls and industrial policy reshape supply chains, alliances, and corporate strategy.

Not Just EVs: China Leads the World in Battery Production and Technology for all Vehicles

How batteries are becoming the enabling layer for industrial electrification and competitiveness far beyond passenger EVs.